A recent study conducted in the United States certainly opened some eyes. Testing on more than 1,200 eagles from Alaska to Florida showed that 46 percent of bald eagles and 47 percent of golden eagles had chronic lead poisoning.

Over time, ingested lead becomes stored in bones. Nearly half of 448 dead birds whose femurs were tested had chronic poisoning, the study said. Older birds had higher concentrations of lead in their bones, which suggests they had multiple, cumulative exposures. While the cause of the ingested lead has not been extensively studied, many researchers are pointing a finger at hunter-killed big game carcasses and gut piles. Eagles often scavenge on the discarded remains of butchered carcasses and gut piles that hunters leave in the field and on animals that hunters wound but don’t recover.

Many of these animals are killed with bullets constructed partially or primarily of lead and hundreds of lead fragments, a result of the bullet fragmenting. These materials find their way into the carcasses and gut piles. Both California and Arizona have banned the use of lead bullets for hunting in condor range. However, the latest study, released in February 2022, undoubtedly will have legislators in both the U.S. and Canada looking more closely at how the use of lead bullets for hunting presents risks to wildlife. We saw legislators react relatively quickly in 1991 in the U.S., and in 1999 in Canada, when lead shot was banned for all migratory bird hunting. Denmark is the first country in the world to place a total ban on lead ammunition. It appears the European Union is making moves to follow. How long will it be until we see similar steps in North America?

Non-Lead Options

Whether you agree with the lead bans or not, the good news is that there are plenty of non-lead options for big game hunters and many hunters are already dedicated users. It can be hard to believe that just 32 years ago, Randy Barnes introduced the first expanding, non-lead, mono-metal bullet: the Barnes X Bullet. Constructed totally of copper with a deep cavity in the nose to facilitate expansion, the Barnes X was touted for its high weight retention and incredible penetration. Looking back in time, the original X Bullet may have been released too early in its developmental stages, because it was not without shortcomings. The biggest issue was that it was extremely finicky when it came to shooting tight groups. Even rifles that shot the X Bullet well at 100 yards often showed dismal accuracy at 300 yards.

Barrel fouling was another valid concern with the original X-Bullet. Unlike jackets on lead bullets, which are made of gilding metal, and a 5% zinc/95% copper blend, the X-Bullets were 100% copper. They had no cannelures, so there was no relief as they passed along the lands. Barrel fouling was real. With the poor-quality copper cleaners available at the time, getting barrels cleaned often required the services of a gunsmith.

The final knock against the X Bullet was that many people believed they were experiencing inadequate expansion, although much of that can be attributed to the fact that people just weren’t used to consistent pass-throughs with their current cup-and-core-style bullets. These bullets were super tough; in hindsight, perhaps they were a bit too tough. They required impact velocities in excess of 2,000 feet per second to initiate expansion. And even with higher velocity hits, there were some legitimate expansion issues with the X-Bullet, especially on quartering shots. Between users not understanding the physics of mono-metal bullet expansion and some legitimate failures to expand, mono-metals gained a reputation for poor expansion that still plagues them today, despite several changes in technology to mitigate this problem.

Second Gen

The TSX was the second-generation mono-metal for Barnes. It sported horizontal grooves that greatly reduced the problem of copper fouling and pressure, and it made the bullet palatable to more rifles in the accuracy department. Since copper is not as malleable as lead, there was a pressure spike with the original X-Bullet. It was caused by increased friction as the bullet came into contact with the lands of the rifling. Incorporating grooves or cannelures into the shank of the TSX reduced friction and the resulting pressure spike, which created a less finicky bullet. Barnes followed in 2011 with the Tipped Triple Shock X-Bullet or the TTSX. The polymer tip is designed to push back into the cavity of the bullet upon impact and facilitate more rapid expansion.

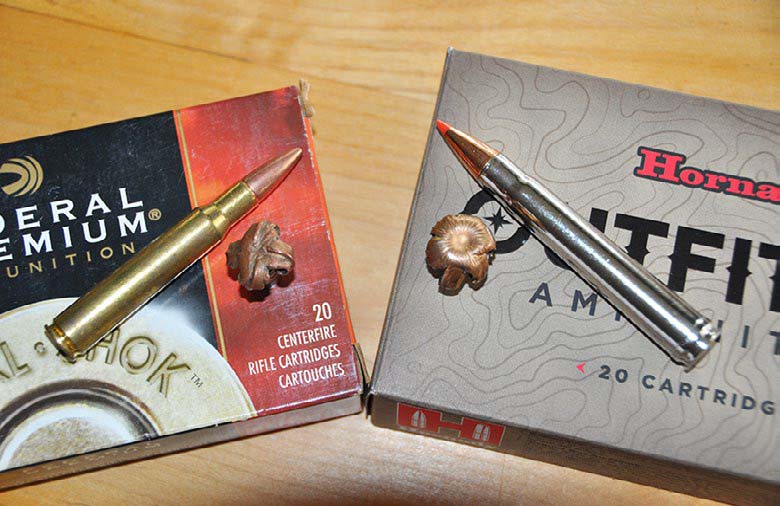

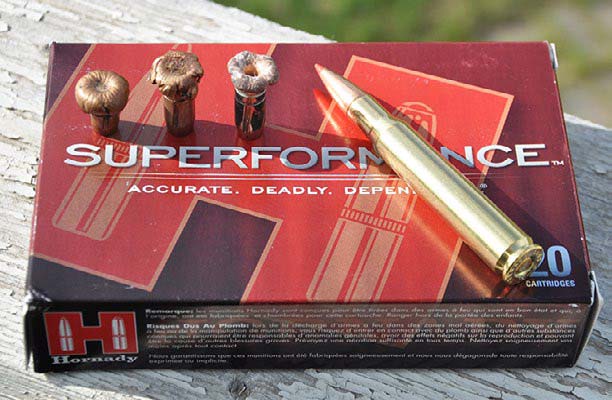

In 2009, Hornady brought their GMX to market. It was constructed of gilding metal and sported two cannelures and a polymer tip. Pressure problems were less of an issue with the GMX. The combination of gilding metal and grooves addressed the issue of copper fouling as well. Regular cup-and-core and bonded lead bullets have a jacket made of gilding metal, so copper fouling is no worse than regular-style jacketed bullets. This combination of features allowed Hornady to push the GMX at the higher velocities associated with their Superformance line of ammunition without pressure and accuracy issues. It quickly became a favorite with those looking to gain extended ranges with mono-metals. Hornady replaced the GMX with the CX in 2022. It is designed to perform better at longer ranges and offers superior accuracy and ballistic coefficient to their GMX, but with the same terminal performance.

More Monos

Following in the footsteps of these early pioneers in the mono-metal bullet development, more companies are adding mono-metals to their lineups yearly. Most ammunition manufacturers now offer at least one version, and companies like Barnes offer four different versions for centrefire rifles.

Certainly, legal requirements in some states are helping to drive this popularity, but so too is a desire for healthier meat. Studies out of Minnesota left little doubt that more traditional ccup-and-corebullets leave large amounts of lead fragments in muscle, and that those fragments can migrate a considerable distance from the wound channel. While no direct link to human health has been made from ingesting lead from hunter-killed game, many hunters prefer to err on the side of caution and go with non-lead alternatives. Manufacturers are responding.

Hunters looking for extremely tough bullets, especially at closer ranges, are big fans of the mono-metals as well. We’ve used mono-metals extensively in Africa, for both plains game and dangerous game. I routinely use it here in North America for moose and bear where ranges are typically fairly close.

Like all bullets, mono-metals have their ideal performance envelope and if you stray outside of it, you can expect less-than-ideal results. They are lovers of speed. While some manufacturers are claiming reliable expansion down to impact velocities of 1,800 feet per second, most dedicated shooters like to keep that at around 2,000 feet per second. Unless you are hunting at long ranges, it’s not a huge concern. Even a 30-06 is capable of those impact velocities out to around 500 yards with a 165-grain bullet. The same goes for accuracy. For the average hunter who never shoots beyond 300 yards, accuracy is more than adequate. However, lead cup-and-core style bullets still rule for long-range accuracy and terminal performance.

Dispelling Myths

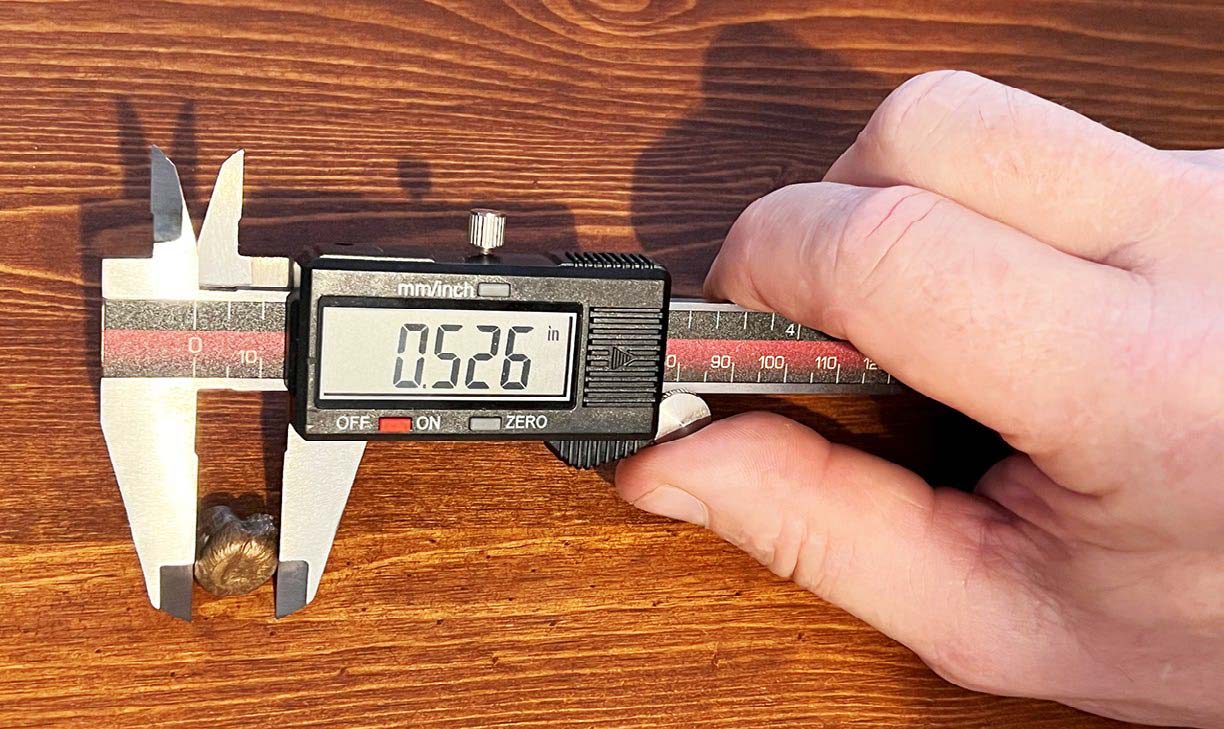

If we look to dispel some of the myths surrounding mono-metals, the first is that the exit hole is only the size of a person’s pinky finger, so the assumption is that they didn’t expand. Mono-metals are tough. They typically retain nearly 100% of the original weight. So, when you get a pass-through, it should be no surprise that the exit hole is no bigger than a bullet that expanded to 2X its original diameter. If you look at a .308 caliber bullet, for example, it will likely expand to around .60 of an inch. My pinky finger is .638 of an inch in diameter. A pinky-sized hole represents a .308 caliber bullet that expanded to 2X its size, not a bullet that didn’t expand at all.

Another common myth is that with close-range, high-velocity hits, these bullets are so tough that they will pencil through without having time to expand. Nothing could be further from the truth. Mono-metals love velocity and the higher the velocity hit, the more rapid and violent the expansion. If you are going to recover a bullet in an animal, it will likely be from a close-range shot. Where you see expansion problems is when impact velocities start to dip below 2,000 feet per second.

Addressing Accuracy

Another misperception about mono-metals is that because they are accurate at 100 yards, they will be equally accurate at 500 yards. This isn’t necessarily true of any bullet, but that is especially the case for mono-metals. Certainly, new designs have done a lot to eliminate destabilization issues at long range, but unless you shoot at long range, you’ll never know. I’ve seen mono-metals in some rifles reliably shoot MOA at 100 yards and have that open up to 2 MOA at 500 yards. It’s not always the case, but it’s a situation that is more common with mono-metals. If you plan on shooting long-range, truth them at long range.

Down in Weight

Another often misunderstood aspect of shooting mono-metals is that you can typically downsize a bit in weight. Since copper is less dense than lead, a slightly lighter copper bullet will be the same length as a heavier cup-and-core. While some rifles may shoot a 180-grain cup-and-core bullet well, they may not shoot a 180-grain mono-metal as well. That’s because it is longer and may not stabilize as well with the rifling twist. But since weight retention is so high in the mono-metal, you can expect better penetration than a similar-weight cup-and-core. With heavy recoil rifles, the drop-in weight can also make them more pleasant to shoot. We run 250-grain GMX bullets in our 375 H&H, versus traditional 300-grain bullets and the reduction in recoil is noticeable.

The final thing that many first-time shooters of mono-metals are surprised about is that animals will often travel farther after a soft-tissue hit. While cup-and-cores often fragment extensively, causing extremely wide wound channels and excessive bleeding, mono-metals don’t fragment. They create a smaller wound channel. While that may be equally deadly, it also may take the animal a second or two longer to bleed out. A fatally shot animal can still cover a fair distance in that additional second or two. With shots that hit bone, you will likely see the animal drop equally fast.

Mono-metal bullets are still relatively misunderstood by the masses. They certainly aren’t the be-all and end-all in bullet selection. For those not shooting long-range who want a super-tough bullet that won’t leave a trail of lead in your meat, they are definitely worth considering. I suspect one day they will be mandatory.

Per our affiliate disclosure, we may earn revenue from the products available on this page. To learn more about how we test gear, click here.