The grouse of my country do not come with a history or a mythology. There are no mossy stone walls, gnarly overgrown apple orchards or second growth paper birch “popple” where “everyday afield is a hallowed memory.”

Nor have they been awarded celebrity status in a Burton Spiller grouse hunting book as the “Thunder King” or “His Majesty the Grouse” – even though there’s a 50 per cent chance that “he” is actually a “she.”

Those are the celestial ruffed grouse of New England, or maybe New Brunswick, which have been attributed super-ruffie powers and cunning intellect.

Acquired, apparently, through decades of natural selection by evading the bird-shot strings directed their way by generations of upland hunters who were a little too slow on the draw. Or so the story goes.

In fact I’ve only encountered one of these glory grouse in all my life that blew out of a wild grape tangle along the banks of the Beaverkill River in the Catskill Mountains while I was on a flyfishing holiday for trout.

It was Spiller and his hunting buddy and fellow author William Tapply who canonized the ruffed grouse and elevated it to deity status.

But come to think of it, that New York bird – once I got my heartrate back down to non-lethal, sub-coronary levels – wasn’t a lot different than one from, say, Lodgepole. That’s not to say that my Alberta ruffies aren’t part of history.

The Milton and Cheadle Expedition, during its epic dash down the North Thompson River, was floundering through the muskegs and aspen uplands somewhere west of the Pembina River where they encountered a bird they called a “wood partridge or willow grouse.”

Which “when disturbed generally flies into a tree.”

“And if there are several together tamely sit to be shot,” the boys noted in their famous 1865 expedition journal. “One after the other.”

Not exactly a right royal ending.

James Carnegie, the 9th Earl of Southesk, in 1859 was on his way to the Medicine Tent River to hunt bighorns when he encountered a small covey along the McLeod River.

“Shot three partridges with my rifle at thirty, ten and 15 yards, hitting all of them in the neck,” Carnegie boasted in his memoir. “As I intended.”

Good gunning, Your Lordship.

In the February of 1859 while on a frigid dog-sled drive from Jasper House to Fort Edmonton, the brains behind the Palliser Expedition, James Hector, was also on the McLeod.

Where before pitching for the night “we found a covey of wood grouse, five in number, and killed them all.”

“Which saved our pemmican tonight.”

Because running out of pemmican, when out on the trail and forced to eat your moccasins, is never a good thing.

Effective hunting, I guess, but not exactly classic.

Hector was a rock doc and first identified the mellow Paskapoo sandstone formation while on the Blindman River earlier in Captain Palliser seminal fact-finding expedition of the west for the British Parliament.

But it is the strata that underlies the buttery-yellow rock quarried to construct the Alberta legislature building – the Belly River, the Viking and the ubiquitous Cardium – that makes or breaks my ruffed grouse.

Because these Crustaceous age rocks are the treasure house of the Western Sedimentary Basin and where all the money comes from. Or at least in the Boreal Forest part of the province.

And not unexpectedly has been seismographed over and drilled into and produced out of for a good part of 70 years by energy companies.

From a ruffed grouse`s perspective, that is not all as bad as you would think on first cut.

All that oil and gas development has created a tangled matrix of well sites, pipe-line rights-of-way and resource roads known around here collectively as Oil Patch.

Mostly on Crown Land.

Sure a few more locked gates and restrictions have been showing up lately following the rise of risk management lawyers and a bout of industrial sabotage a few years back.

But for the most part it’s accessible – so long as you keep in mind that this remains a working industrial landscape and use a modicum of common sense.

The unintended consequences of all this industrial activity over all those years – a landscape that the Alberta Energy Regulator has identified as “aging infrastructure”- has been the creation of hundreds – maybe thousands – of kilometres of prime ruffed grouse habitat known collectively as “edge.”

Where the mixed-wood forest intersects with open ground. Not unlike Spiller’s Vermont walls and orchards, grouse love hanging out in edge.

Next, throw in a food source, another unintended consequence of oil and gas development where disturbances are managed for minimum impact and resource companies are compelled by government regulation to maintain something called “equivalent land capability”.

So, any disturbed land must be quickly revegetated to contain erosion and restore habitat with a seed mix that in the past invariably contained red clover.

Oil patch ruffies have grown over time to love red clover leaves and come out to the oil road ditches and lease sites to load up on the stuff.

See where I’m going?

Especially in the fall before the killing frosts when the clover lies in a lush, green and succulent rug.

Specifically, in this aging oil patch which an AER directive describes as “pumpjacks that aren’t pumping, pipelines that aren’t transporting and gas wells that are closed off.”

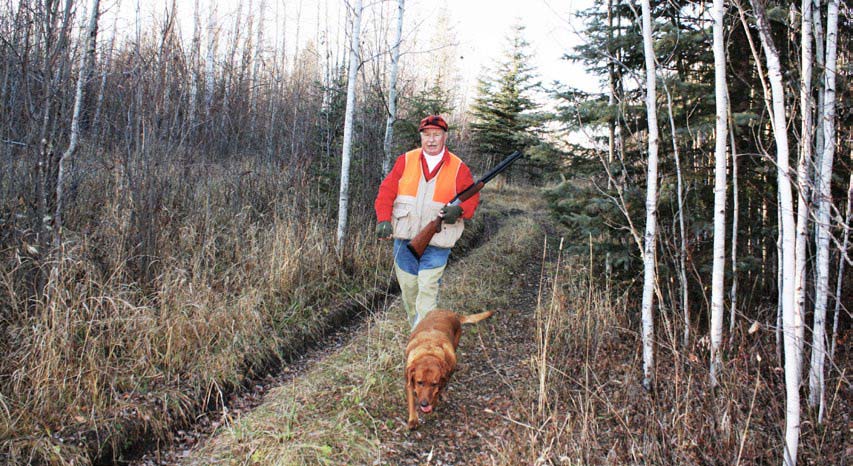

It’s the next best thing to ruffed grouse nirvana and I`ve come out to a tired old corner of the historic Pembina Oil Field south of Lodgepole in west central Alberta to exploit it with my fox red Lab Penny.

And hopefully harvest a few Industrial Strength ruffed grouse.

Here the oil wells have passed through a multitude of owners as corporations merge, thrive, fall or go bankrupt.

Many bearing exotic Texan names like Bethlehem, Lufkin and Continental Emsco lie silent in regulatory limbo. Some stripped of their Jurassic pumping units altogether.

Others pitched at chaotic angles by the frost heaves.

The roads too, are in a suspended state. Subject to only minimal maintenance.

Nature abhors a vacuum and the clover mats have expanded from the ditches encroached the road surface. It doesn’t get much better for a grouse.

I park the Jeep at the corner of an inactive wellsite, lift the hatchback for the dog and drop two 12-gauge grouse loads into the chambers of my Ruger Red Label.

And we are off.

A lot of Alberta grouse are harvested in the manner of Milton, Cheadle, Carnegie, and Hector.

With a .22 and often as a pleasant distraction while on a big game hunt. Nothing wrong with that.

As a homage to the New England guys or maybe just my nostalgic world view, I prefer an over-and-under double gun over a willing dog.

My dogs, for better or worse, have always been flushing Labradors.

And lately my shotshells have been a throwback too after Challenger Munitions out of Saint Justine de Newton, Quebec began reissuing the cosmic royal blue Imperials.

Sure, the colour isn’t a perfect match to the seminal CIL ammo of my youth and the paper casing and two sublime milled bands around the high brass have also gone missing. But they are sweet, for sure.

Part of the mystique – and agony – of ruffed grouse hunting is the flight of the bird once flushed as it heads for the sanctuary of the tall timber.

Where shots, especially the second barrel or third shell in the chamber are more times than not taken through a screen of dogwood, hazelnut or second growth poplar.

And the more balls you have in the air the better.

Unlike Canada geese or cock pheasants, ruffies are relatively easy to kill.

It’s getting one or two pellets on target that’s crucial. There are a variety of loads that can get the jobs done, of course. Each to his own.

But I prefer a cartridge with a little more steam in it that a standard target load.

Like the Imperial or other cartridges designated as a “heavy upland load.”

For no other reason than a shell with a jacked-up powder charge will allow the string to penetrate the understory better.

In 7 1/2 shot-size so a maximum number of pellets can be launched at the little brown target doing hockey dangles through the underbrush. Then hope for the best.

Not all Alberta Oil Country is Grouse Country, so it’s best to focus your hunt in terrain where grouse population tend to congregate. Clover, of course, it the key component. But so are aspen poplars. Alberta grouse owe their survival to aspen buds which is their primary winter food source.

Penny charged off ahead of me, working the ditches and forest edge for scent.

With grouse hunting it a matter of putting the dog in likely looking cover and letting her do her thing.

Once she cuts a hot scent, she will let you know.

I have spent countless hours of hunting bliss looking at a Lab’s butt while the dog did his or her thing.

And I could not think of a better place to be.

We hunted along a winding road lined with poplars and white spruce that led to a complex of well sites.

Then Penny’s nose hit the deck. Her stubby tail began beating against her sides and she charged off into the woods. I heard the bird lift off before I saw it, swung the gun towards the sound and thumbed the safety tang.

When I finally saw it, the grouse was already in the evergreens and the shot was borderline at best.

I squeezed off a round anyway, but dog came back with no feathers in her mouth.

More than any other game bird, oil patch ruffed grouse hunting required fast, maybe even instinctive, shot gunning. And the only way to get good at it is to do it.

Which always means knowing where your dog and your hunting partner is, always and practicing disciplined firearms safety.

Specifically, with trail birds, which changes are good will flush low and along the road for a few metres before banking into the cover – with the dog usually in hot pursuit. No shot.

While stressing again, mature Oil Patch may be appeared to be abandoned and forsaken, it remains an industrial landscape and subject to occasional inspections by energy company personnel.

The second bird, which was back in the forest, made a similar miraculous escape.

Same with the third and I was beginning to cast serious doubt on my skill sets. Not unusual when I am on the grouse trails.

But Flush No. 4 fell to a string of Imperial 7 1/2 shot and Penny gave me 13 flushes and two more birds before we arrived back at the truck several hours later.

The Alberta ruffed grouse season is surprisingly generous stretching from Sept. 1 in many Wildlife Management Units (a week later in most others) to January 15.

While you can harvest birds throughout the season Prime Time is that mercurial few weeks in late September, October and early November between when the aspen leaves have mostly come down until the first permanent show dump of winter covers the clover and sends the birds to seek refuge in the poplar canopy. Although in the Chinook belt closer to the mountains this can be extended.

The limit is a relatively generous five daily and 15 in possession.

One curse and blessing about Alberta grouse is that their populations are highly cyclic. Spiking and crashing like no others in North America for reasons many scientific theories abound but nobody really knows for sure.

So, every seven years or so there are birds everywhere. Usually followed by a few lean falls where you have to put on a lot of klicks on your hunting boots to put a little weight in your vest’s game pouch.

And save your supply of pemmican for another day.

By Neil Waugh

Per our affiliate disclosure, we may earn revenue from the products available on this page. To learn more about how we test gear, click here.