The pool was long by mountain standards. With water levels low, the water barely moved. I had been fishing for a few minutes before I noticed a heron across the stream from me. It was fishing, too.

Hardly moving, the bird stared into the water, its neck cocked. Suddenly, it uncoiled like a snake and struck, emerging from the stream with a foot-long rainbow. Holding the fish momentarily, the heron then flipped it into the air and caught the trout in its beak head first, swallowing it in two gulps. I suspected the heron was catching more fish than I was.

Late summer and early fall fishing on small streams requires wading with stealth, especially if you pursue brown trout. Browns like to lie in shallow water and beneath undercut banks, spooking at the first disturbance. To approach such fish, you will find no better example than the heron.

Stealth basically comes down to sight and sound, or better yet, the lack of it. Trout spend their lives eating and avoiding being eaten. They sense danger through sight and sound, these being the clues that predators are close by. But if a heron can get close enough to catch a trout, perhaps we can get close enough to cast to one.

Often, fish see predators through movement. This is a challenge for fly fishermen who have to wade and wave a fly rod to cast. Carefully moving through the stream, especially in slow water, helps. So does minimizing false casting. One way to reduce false casting is to use a water haul, where you let the drag of the stream from behind you load your cast and simply flip your line into the pool without a false cast.

Bright clothing has become fashionable in fishing circles, but on small streams, these may work against you. Drab colors contribute to stealth. If you think about it, pursuing spooky fish in shallow water is almost as much like hunting as it is fishing.

Also, predators of fish typically come from above, so it helps to avoid creating shadows over the water. Fly lines throw both shadows and mist during a false cast, so it pays to keep your false cast away from where you want it to land.

Regarding sound, moving slowly helps to minimize splashing and pushing ripples across the water. Likewise, the sound of grating rocks underfoot is louder than you might imagine.

Kevin Howell, owner of Davidson River Outfitters, has been guiding in the western North Carolina streams since the early 1980s. He once commented in a fishing seminar that swimming in mountain creeks as a kid taught him how loud grating rocks can be. Is is especially so in heavy-pressure water, and so he emphasizes moving quietly.

One midsummer afternoon, I was about to quit fishing as the sun had risen and shone brightly on the stream. I was resting on a rock at the bottom of a pool when I noticed the slightest dimple on the other side in the shade. The fish seemed to be sipping midges.

Without leaving the rock and stepping into the water, I sent a few false casts over the pool and then dropped an inchworm down a couple feet above the sipping fish. The fish bolted forward, leaving a wake in the shallows, then it took the inchworm.

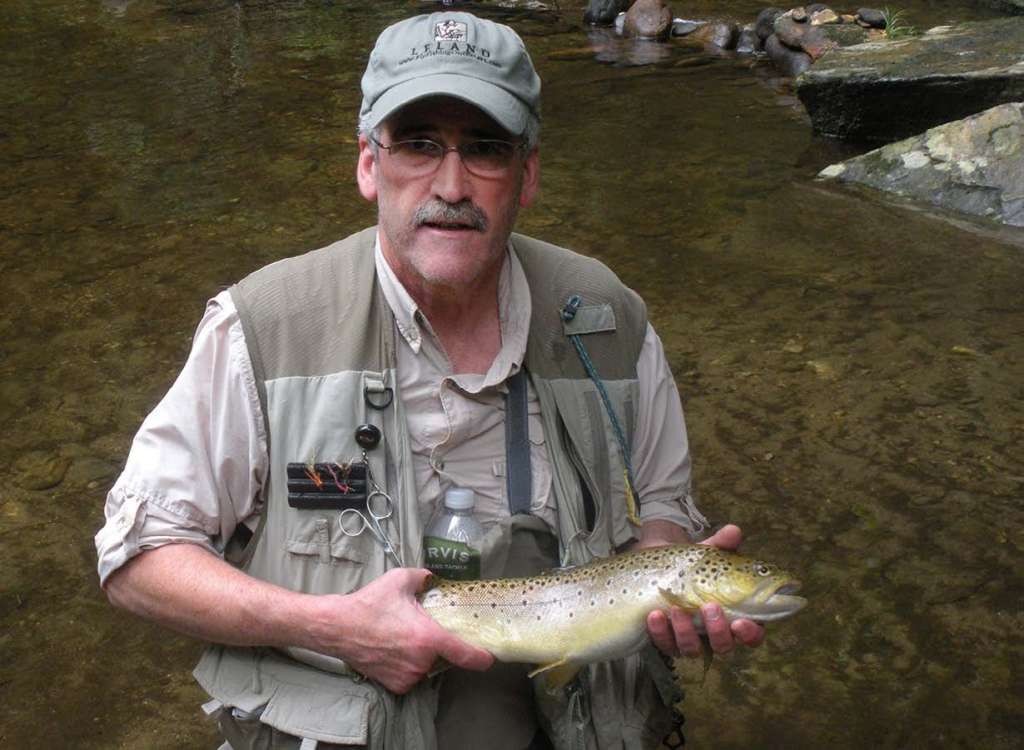

The wild brown knew the pool better than I did, and tried once or twice to head into underwater obstructions. But after a few laps, it finally conceded and came to the net. Keeping it wet and letting it revive, I admired any fish that could survive this long in a small stream.

I didn’t measure the fish and it has grown since then (at least in memory) so I won’t wager a guess to its size. Perhaps what is most remarkable is that my best fish on that stream came under the most trying conditions.

Looking back, stealth played a larger role in catching that brown than anything else. I had been unconsciously resting the pool and remaining still. Standing in shadow, I cast to the shadows. Nothing overhead spooked the fish. And by casting from the rock where I sat, I didn’t disturb the water or grate on gravel in the pool.

I figure the heron would have approved.

Per our affiliate disclosure, we may earn revenue from the products available on this page. To learn more about how we test gear, click here.