How to Be an Accurate Shooter for Big Game

As I crawled over a small rise on the prairie landscape, the herd of antelope was casually grazing on the short, protein-rich grass. The rut was coming to an end, but a couple of bucks were still showing a bit of interest in one doe. We’d spent the better part of three hours duck-walking and crawling to get into position on these antelope. The rangefinder in my binoculars read 479 yards. It was a long shot at a small target, but it was also something for which I was well-practiced.

I extended the bipod legs on the S90, dialed the Zeiss scope up to 18 power and spun the turret to 475 yards. I slowly slid the bolt back, and then forward again, feeding the chamber with a 6.5PRC round, I was on autopilot from this point.

There’s an old adage, “Aim small, hit small.” But as the crosshair settled on the antelope’s side, there was no red circle or black X to guide my aim. There was nothing small at all for this aim. There was just an entire animal, and I knew there was about an eight-inch kill zone in the area right behind the shoulder. All I had to do was place the crosshair roughly in the middle of that kill zone and gently squeeze the trigger. There was no need to aim small. Aiming big was critical, since it allowed me to keep the kill zone in context with the rest of the animals.

As the crosshair settled just behind the front leg, my finger tightened on the trigger. Two-and-a- half pounds of pressure is almost imperceptible to the novice shooter. But when you spend enough time with a rifle, you know when you are about to exact precisely that amount of pressure on the trigger.

Some shooters say they like to be surprised when the trigger releases the firing pin, setting in motion a chain reaction that sends the bullet downrange. I like to know the exact millisecond that it’s going to happen. And as my finger reached that point, I could see the crosshair steady on the target on a patch of brown hair. The big buck folded at the impact of the 143-grain bullet and never even kicked. It had taken me 13 years to draw this permit. The moment played out exactly the way I’d hoped.

Shooting 1000

I shoot a lot. I generally put over 1000 rounds downrange each year and maybe 10% of those are at paper targets. Accurate rifles impress me, but the truth is, a rifle that shoots MOA or a one-inch group at 100 yards is more than adequate for the hunter who never shoots over 500 yards. Social media is filled with pictures of targets depicting sub-MOA groups; you don’t dare post one that is only MOA for fear of being attacked. A lot of shooters have lost sight of the realities surrounding shooting in an actual hunting situation. Some don’t get off the bench enough to practice real-world shooting skills. Shooting tiny groups can get addictive. So can the accolades on social media. But aiming small is not a skill that serves you well in the field.

Some Facts

Let’s look at the facts. The first is that a deer-sized animal has a roughly 10-inch diameter kill zone. Place a bullet inside that 10-inch zone and you will have venison in the freezer.

The next fact is that deer have no point of aim that your eye is drawn to like you see on a paper target. So, you need to be able to identify that 10-inch kill zone then place a bullet inside of it without help from a red circle or a black X.

The odds of that animal standing perfectly still for two additional shots so you can claim a sub-MOA group is approximately zero. Sure, I understand the value of working up a load and having your rifle shoot as accurately as possible. However, that accuracy does not transfer to a hunting situation. The best-case scenario is that you’ll be shooting from a prone position or from a bipod. In a real hunting situation, it’s more likely that you’ll be leaning on a tree or shooting from sticks. No shooter—no matter how skilled—is going to transfer their bench accuracy to these field conditions.

I use the bench to find an accurate load and establish a 200-yard zero. After that, I never shoot that rifle off it again unless I want to check zero. Bench shooting is a skill all its own. Other target-shooting disciplines are too, but just because you’re good at one doesn’t mean you’re a skilled shooter on game in the field. If you’ve never had to pick a large target area on a live animal (versus a tiny target area on a piece of paper), it can be a lot to process. I’ve seen some true disasters occur for incredible bench shooters when they find themselves looking at a live animal through the scope for the first time, especially if things are happening fast. (It seems they often are.)

Getting Proficient

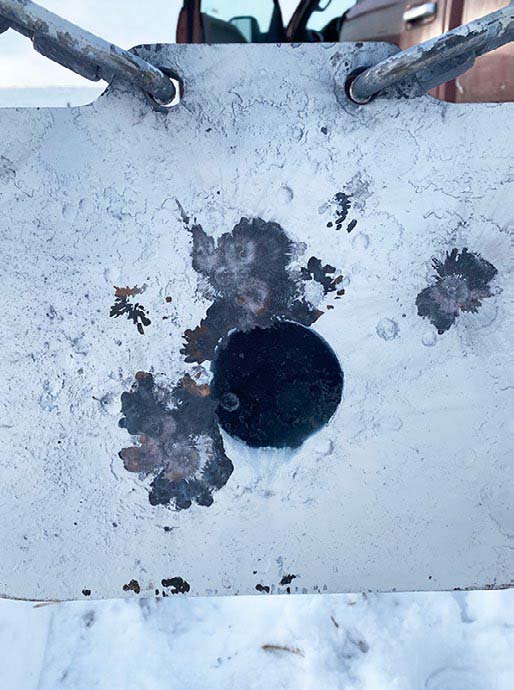

Now, if you want to be proficient in a hunting situation, you need to practice under hunting conditions. This includes getting away from traditional paper targets. My favorite targets are made of steel because they are reactive. There’s just something about the reward of hearing the ring that a solid hit makes that is so satisfying. The bulk of our shooting is done at a steel plate that is suspended by chains. While we’ll sometimes put a black dot on it to confirm long-range zeros, we just practice shooting at center mass for the most part.

Lessons from Namibia

No matter what position or range you’re shooting from, I like to practice getting shots off as quickly as possible. When we hunted Namibia in Africa for the first time, our professional hunter told us that from the time you committed to getting up on the sticks, you had about five seconds to mount the rifle, find the animal, place the crosshairs, and make the shot. We now call it the five-second rule and much of our practice is based upon that concept. Being that rushed quickly makes you find the center of the kill zone and forget about aiming small. You learn to aim big, and as long as you are close to the center of a 10-inch steel target, you’ve got your game. I find this is where target shooters really struggle. While their events are timed, they are not that rushed, and rather than just looking for a 10-inch target, they are looking to aim much smaller with much more precision.

I hunted in Finland recently and hunters in search of moose there are required to pass a shooting proficiency test prior to obtaining a license. They must place three shots in a moose target at 80 meters in under 90 seconds. I practiced for this quite a bit before going to Finland. At first, 90 seconds sounded like a short period of time. When I completed my first practice round, I was shocked to see the timer said 17 seconds. It was just a matter of employing the principles we were taught in Namibia. On the moose target, the vitals were close to 24 inches in diameter, so it was relatively easy. The trick is not to get bogged down searching for that small spot to aim. Instead, aim big and hit small.

Get Paper Targets

For the absolute novice hunter, regardless of how much shooting experience they have, it’s worth investing in some life-size paper targets of the animals you’ll be hunting. Ensure these targets don’t have aim points on them. At first, practice from 100 yards by just getting into position to shoot, then placing the crosshair. Once you’re comfortable with that, move on to actually shooting at the target. For some bench shooters, this can be a pretty humbling experience when their .25 MOA groups open up to four or five inches. It’s hard to convince them that this is acceptable accuracy in a hunting situation. Having the shots placed in the kill zone is all that matters.

As I write this, we are only 56 days from heading to Africa. We are going to be doing a fair bit of bow hunting there in addition to some rifle hunting. The same principles apply. Don’t worry about shooting a perfect 10x with every arrow. Just worry about getting your shots in the 10-inch kill zone. The bulk of our shooting before we go will be done at life-size targets with no identified spot to aim. While shots will be slightly less rushed than with a rifle, we try not to waste any time aiming for those small spots. Find the vitals, place your pin on them, and release. Equally important is doing practice shooting outdoors. where you’ll be dealing with a host of environmental factors that you don’t experience when practicing indoors.

There’s no rocket science here. In many ways, it’s dumbing down the way you shoot. Stop looking for super-tight groups to post on social media and just worry about being in the kill zone. Once you make this transition, you’ll find yourself becoming a much more proficient hunter.

Yup! Aim big and hit small, that’s what I say.

Per our affiliate disclosure, we may earn revenue from the products available on this page. To learn more about how we test gear, click here.