As great as a nicely functional, good casting rod can be, the rubber hits the road to the greatest degree with your fly reel. Get a bad reel and you’ll suffer nothing but frustration and lost fish. A good one, on the other hand, can let you completely forget about that aspect and focus on what really matters: the fish. Let’s look at how you can end up with a great reel.

Fly reels consist of a few simple parts. There is a body or housing, a spindle, a drag system, and a spool with a handle (or two), and/or possibly a counterbalance on the spool.

Fly reel housings and spools are pretty much all made of aluminum. Aluminum fly reels can be made of cast aluminum, which is poured into a mold to form the part, or it can be milled from solid bar stock. Both techniques work for their intended niche. However, both aren’t cheap, so you need to consider the purchase of a cast reel when your fishing needs call for a stronger one (i.e. salmon fishing.)

Aluminum components in the reel may or may not be anodized. Anodizing is an electrolytic process that hardens the outer surface of the aluminum, making it tougher and more scratch and salt resistant.

All reels have some steel components (like the spindle), and those parts should be made of stainless steel. Some reels incorporate plastic parts. That’s okay, depending on what those parts are used for. Graphite is also used in some reel drag systems. You should avoid low-end reels that contain components of standard steel and non-anodized aluminum components, however, since those parts will rust or corrode over time.

If you are going to fish salt or brackish water, be intentional in seeking out a reel that is saltwater certified or saltwater “friendly.” Manufacturers will all ensure that you know if it is and if the warranty covers saltwater damage or not. Regardless of whether you will be fishing the salt or not, always make sure the aluminum is anodized.

There are only really a couple of characteristics that you need to focus on when searching for your fly reel: type of action, type of drag, and type of spool.

Reel Actions

Fly reels come in three actions: single, multipliers, and automatics:

- Single action: Single action reels are simple. They have no internal gears. Every 360-degree turn of the handle winds the spool one turn of 360 degrees. This is referred to as a 1:1 retrieve ratio.

- Multiplier action: Multipliers, as you may suspect, are like spin-casting reels; for every 360-degree turn of the handle, the spool turns more than once around. The ratio can vary from manufacturer to manufacturer; 3:1 ratios are common. These reels have internal gears. I don’t like gears; they get full of sand and stuff and are favorite targets of Murphy’s Law. Buy them at your own peril.

- Automatic action: Automatics are spring-loaded. Basically, they have a coil return spring inside, sort of like a tape measure, that engages the spool when you press a button and the reel spool spins on its own under the power of the spring to pick up any slack line you may have laying about when you hook a fish. I think of this action as the Monty Python action…“Run away, run away.” I won’t say any more about it.

Drag Systems

There are two types of drag systems common to fly reels: pawl (or ratchet/click) and disc (or friction):

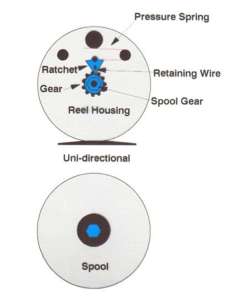

Pawl Drag System: This drag system consists of a pawl or ratchet that looks a bit like a triangular tooth that is held in place on the reel housing by a pin at the pawl’s base. The pawl pivots on the pin. The point of the pawl sticks into the teeth of a gear that turns around the base of the spindle as you turn the handle. Somewhere on the housing outside of the pawl will be a spring. The spring will press on one or both edges of the pawl, restricting the pawl from pivoting. The spring’s tension or pressure is controlled by the adjustment knob that goes through the housing to the back of the reel where you can adjust it manually. The more pressure the spring applies to the pawl, the harder it makes it to turn the spool. Simple, and it is an old and reliable drag system, but it does have its drawbacks:

- The tip of the pawl and the teeth of the gear can wear over time and so the drag slowly becomes less effective and will finally be useless as the points wear out.

- If you fish for big, fast-moving fish, like Coho, then the spool can end up being spun so fast by the fish that the pawl never has a chance to settle into the teeth of the gear. It just rides over the top of them, thus your drag becomes useless just when you may need it the most.

Pawl drags can come in unidirectional or bi-directional types. Uni-directional drags only apply the drag when the line is pulled out. Bi-directional drags apply drag reeling in and pulling out. This depends, as I mentioned, on whether the pressure spring applies pressure to one or both sides of the pawl.

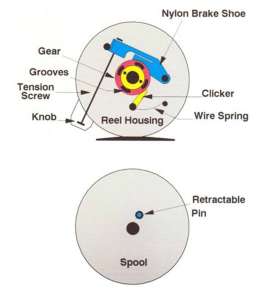

Disc (Friction) Drag Systems: Disc drags are designed to work like your car’s brakes. Somewhere in the system, there will be one or more discs that rub on a shoe (drum brake style) or rub against each other (disc brake style). As you adjust the tension by turning the adjustment knob, the pressure increases between the shoe and the disc or between the two discs. It is simple and works well.

The shoe and discs can be made of different materials, from graphite, to nylon, to stainless steel. What is important is that the drag still works when the discs and/or shoe get wet. I’ve heard many reports of disc drag reels slipping or pulsing when wet.

Do a little research on the internet before you buy. Looking up the reviews by others can help a lot in making a choice. Reel drags are often a “you get what you pay for” situation, within reason. This is where you get your money’s worth… the disc drag system. Disc drags are, by far, the most common drags in better reels. They are almost always unidirectional, engaging only when the line is being pulled off the spool.

Regardless of the drag system, the drag should be adjustable. Extremely low-end reels can still come with drags that cannot be adjusted, but if you find one just leave it, it’s not worth the money. And here is a tip: back the drag pressure off to nothing when you have finished fishing or when you store the reel; it’ll preserve your drag longer.

When you look at buying a particular reel, try to see how adjustable and how smooth the drag is. This is important. Some reels are not infinitely adjustable, which simply means they adjust in steps. You can feel it. As you turn the drag adjustment knob it will either turn smoothly as you very slowly tighten and loosen it or it will feel bumpy. If it is bumpy, then it is adjusting in steps. I much prefer the infinitely adjustable drag.

In addition, the drag must be smooth. This is hard to tell if the reel has no line on it. Ask to string the reel with some line or see if you can somehow test the drag by pulling line off the reel under tension from the drag. If it does not come off evenly and smoothly, then don’t buy it.

Spools:

Spools come in two types: the enclosed rim or exposed rim. When the spool is attached to the reel housing by sliding it onto the spindle and seating it, the rim of the spool will either fit into the rim of the housing (thus preventing the spool rim from being touched while fishing or playing a fish) or it will fit over the edge of the housing leaving the rim exposed while fishing. This feature is not all that important, and it is really dependent upon how you like to play your fish. Some anglers like to let the reel drag do all the work while others like to have more control over the drag tension at any given time, and like to “palm the reel.”

Anglers who like to palm the reel place the heel of their free hand lightly against the exposed spool rim and increase that pressure to add drag as they deem it necessary while playing a fish. It’s fun, and if you mess it up, you can break off your fish…your choice. I prefer exposed spools. I like having fun and feeling like I have more control (even though I probably don’t, when it comes right down to it.)

The other feature to look for on the spool is a counterbalance. It will be attached to the outside face of the spool 180 degrees across the spool face from the handle. Since the reel handle has a weight to it, centrifugal force will cause the reel to bounce when the spool spins quickly as a fish pulls out line.

To stop this, the companies either add a second handle op

posite the first or attach a counterbalance that weighs the same as the handle on the opposite side of the spool. If the reel doesn’t have a counterbalance or a second handle, I would not buy it. Leaving off the counterbalance is a good way for a company to save money and is a sign of cutting corners; it’s a good early warning of a cheap product.

There are a few other things to consider when hunting down your reel. You should think about the location of the drag adjusting knob and its size. The knob should be on the back of the reel and, in my opinion, the bigger the better. It should be on the back of the reel so that your hand does not have to try to adjust the knob on the same side as the reel handle when it is spinning 100 miles per hour as a fish is tearing offline; that can result in badly rapped knuckles, and maybe even a broken-off fish, if the handle hits your hand while you are trying to adjust the drag.

The size of the adjusting knob is important too because you don’t want to be feeling around for it or looking at your reel to find the knob when playing a fish that is taking line.

Arbours:

The center part of the spool where the line wraps around is called the arbour. Fly reels come in standard and large arbor sizes.

Large arbor reels have a larger diameter arbor, which means that when the line is reeled in, more line comes in with every turn of the spool. This helps when you are frantically trying to reel in slack line as the fish is running toward you.

However, to accommodate the same amount of line with the oversized arbor, the reel spool must be wider, so you end up with a fatter reel overall for the same weight and length of line. I like large arbor reels for larger fish; trout are just as fun and just as effectively reeled in with a standard arbor reel, unless you’re fishing for very large trout. Again, it’s a personal choice.

Lastly, you need to ensure that the reel’s direction of retrieve can be reversed. There are still some reels out there that do not have this feature. You want the direction reversible in case you reel left-handed, or when you are right-handed, like me. Traditionalists will reel right-handed if they are right-handed; I have no idea why, but that is the way it is. The manufacturer’s description of the product will always tell you whether you can reverse the direction of the wind, and how.

To summarize: lower-end reels (usually less expensive) will usually be made of cast aluminum, be single action, have pawl drag systems, will not be saltwater guaranteed, will have small-stepped drag adjustment knobs, and standard arbor spools. As you go up in price, different features become available. For my money, I look for a saltwater guaranteed, solid bar stock, single action, reversible, infinitely adjustable disc drag reel. If it is for steelhead or salmon, I want a large arbor as well.

Take my advice and get a good reel. You won’t regret it.

By Bill Luscombe

Per our affiliate disclosure, we may earn revenue from the products available on this page. To learn more about how we test gear, click here.